In a strange cinematic convergence, that feels hardly coincidental, three mainstream films currently in US cinemas feature extremely privileged people on islands on which things go horribly awry. Menu, Triangle of Sadness and Infinity Pool, each unfolding in their own desperate echo chamber, resound with a telling doomsday knell capturing much of the present cultural moment’s anxieties of late capitalism and the Anthropocene. The directors Mylod, Östlund and Cronenberg depict three iterations of essentially the same tale: a hermetically sealed enclave of the haves is thwarted by the have-nots, in a darkly Hobbesian struggle for power that careens towards cataclysm. Through edgy art direction and clever conceits of revolts against hierarchies or circumventions of power, this triumvirate of directors attempts to lambast the status quo, while their high-budget, heavy-carbon footprint, star-studded productions, emphatically and ouroborically perpetuate it. Nature on their islands is alienating or menacing and the overall visions are disturbingly dystopic.

Fortunately, one new island film offers an alternative worldview that, if not entirely utopic, is certainly more hopeful and life-affirming. Geographies of Solitude, by director Jacquelyn Mills, traces the relationship between the naturalist and environmentalist, Zoe Lucas, and Sable Island (Canada), her home for the past 40 years, providing a mesmerizing diaristic account of her idyllic, radically purposeful and mostly solitary existence. This breathtakingly beautiful experimental documentary radically departs from the traditional modes of nature film, biography and documentary, forging new expressive possibilities for politically engaged cinema and challenging us to rethink our relationship to nature.

As the two sole human inhabitants of Sable Island during the time of filming, Mills and Lucas ground Geographies of Solitude in a female subjectivity, in effect reclaiming the island as a feminine space. To viewers steeped in the European imaginary of islands as sites for performing masculinity — in which women are completely absent (e.g. in Robinson Crusoe), or serving as sirens, sorcerers or supporters for the male hero (e.g. in the Odyssey and The Tempest) — Lucas, as self-determined sovereign of her own solitude, feels revelatory. Near the film’s end, the landing of Jacques Cousteau in a helicopter (named “Calypso”), from archival footage of a 1981 visit, is a jarring, but brief, rupture in this unspoken sisterhood. Having obscured her face throughout the film, the full-face view of a fresh-faced youthful Lucas we see in this Cousteau clip is a welcome but equally jarring moment of the male gaze.

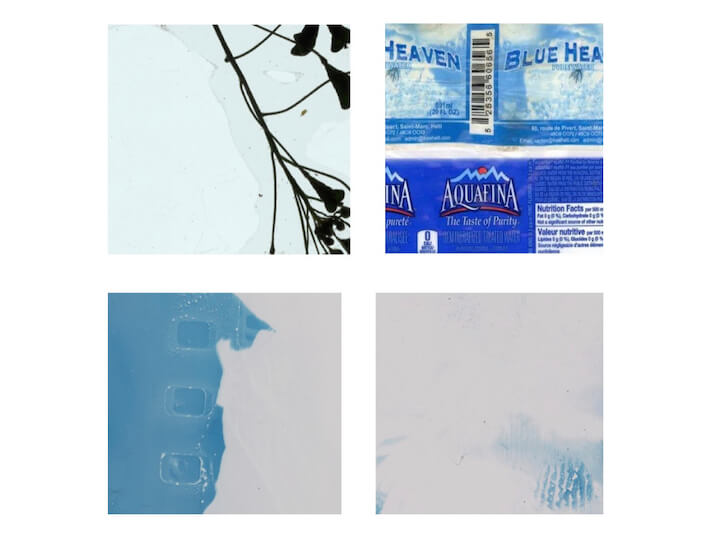

As collector and cataloguer of the ebbs and flows of the island’s wildlife and marine litter, Lucas’ work oscillates between the scientific and custodial. Recipient of an honorary doctorate for her work, her dedication to documentation lends itself however to labor that often feels domestic. Meditatively gathering, sorting and cleaning the shoreline detritus, Lucas mentions, “it’s not an unpleasant chore; it’s kind of like knitting.” Loads of colorful marine plastic, handwashed and hanging on the clothesline, blow in the breeze like ethereal otherworldly laundry. Shards of beach glass and plastic are transformed into jewel-like light-catchers.

The film’s stunning visual richness reminds us that, at heart, it is a collaboration between two artists (Lucas received an MFA in 1977). This aesthetic sensibility of both women fosters arresting images that would be at home in a gallery or museum: tangled masses of fiberoptic cables washed ashore mimic a forlorn sort of Land Art; Mills’ shots of celestial starry night skies and terrestrial horse dung and Lucas’ documenting of the horse skulls and bird corpses recall sculptor Kiki Smith’s installations of bleached bones, dead crows, stars and scat.

In Lucas’ logging of detailed data on each animal, she offers little gestures that, in their practicality, resemble care: birds get burials and horses get names. Her role extends beyond mere scientist to that of steward. She points to the “bursts of vegetation” that spring forth from the animal corpses that in turn nourish the next generation of wildlife. Her vision of the island as a regenerative space is one of the many rewarding aspects of the film, presenting a framework for coexisting with nature and transcending Eurocentric binaries of nature/culture and utopic/dystopic.

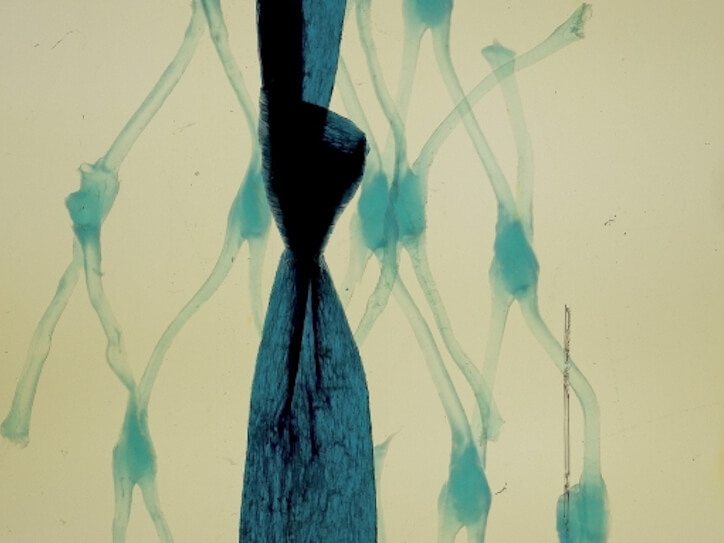

Coexisting with nature means reducing one’s carbon footprint, one that for the filmmaking industry is enormous. As a nod towards alternative greener strategies, Mills implements eco-friendly filmmaking techniques, engaging with the fledgling field of “permacinema.” Sequences using the local flora and fauna, such as “Horsehair, bones and sand; exposed in starlight; developed in seaweed,” are reminiscent of preeminent “artisanal” filmmaker Philip Hoffman’s plant-tinted and processed films. But Mills pushes the techniques further, incorporating them into the film’s unique idiom, creating astonishingly beautiful images, as well as enchanting “music,” ingeniously created by electrode-recorded movements of local snails and beetles.

Perhaps the most inventive aspect of Geographies of Solitude is its singular way of navigating across and through the formal and tonal constraints of genres: it avoids the colonialist gaze of the nature program, dodges the alarmism and didacticism of conventional enviro-docs, eschews the escapist despair of eco-disaster flicks, sidesteps the landscape kitsch-porn of eco-epics like Koyaanisqatsi and forgoes the pitfalls of pure materiality in experimental film. In the end, Mills succeeds in creating something formally hybrid and tonally new. Without sentimentality Mills shows the same profound empathy and honor for her subject that Lucas shows for the ecology of the island. Mills’ film acknowledges environmental threats without stridency or doomsday gloom. By nesting the political within the poetic, and grounding her work in empathy and regenerative possibility, Geographies of Solitude points the way to a more equitable and ecologically conscious future. If you missed the film in its NYC theatrical run at Anthology Film Archives in January 2023, don’t miss it this week at DCTV (a terrific documentary screening center housed downtown in a beautiful old firehouse). Geographies of Solitude is a must-see.

Geographies of Solitude by Jacquelyn Mills, 2022, Canada,103 min., DCP

March 7-11 | Firehouse Cinema at DCTV, 87 Lafayette Street, NYC

by Maya Han